|

April 2019

|

|

|

Texas Department of Transportation's Focus on Planting Native Plants

Many people see invasive plants growing along our Texas highways and naturally wonder whether the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) is responsible for planting them. Because of this, iWire asked TxDOT to contribute an article on its approach to managing vegetation in its rights-of-way. Dennis Markwardt, TxDOT, and Forrest Smith, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, kindly submitted the following article. Please keep in mind that the vegetation along any particular stretch of roadway is a complex reflection of historical and current management practices, and of interactions among the plants, the environment, the weather, and neighboring vegetation. Also keep in mind that TxDOT, like all our State agencies, has funding and staffing limitations. - Ed.

The Texas Department of Transportation is one of Texas’ largest land managers, overseeing more than a million acres. An important component of their stewardship is restoration and maintenance of vegetation on state rights of way. Since the early 1900s, TxDOT has worked to encourage wildflowers and native plants along Texas roadsides. Maintaining roadside vegetation cover to meet the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, Noxious Weed Act, and Executive Order 13112 while meeting TxDOT’s mandates to maintain a safe, reliable, and aesthetically pleasing roadside environment is a huge task. Some of the many maintenance efforts involved to achieve this mission include seeding over 30,000 acres of wildflowers annually, careful oversight of mowing schedules, facilitating horticultural plantings using native species, and selective application of herbicides to maintain visibility and limit invasive plants.

In addition, TxDOT is charged with overseeing revegetation operations that are an integral final step of the highway construction process. Historically, in line with the prevailing land uses of the day, TxDOT utilized non-native grasses in such seedings in much of the state. This use was influenced greatly by seed availability. For much of the last century, the only seeds available in quantities needed by the department for erosion control plantings were introduced forage grasses, late-seral native species that were difficult to establish, or annual grains.

As times have changed when it comes to Texas land uses and desired vegetation, so too has TxDOT. One of the greatest limitations to using native plants in revegetation endeavors, for TxDOT and landowners, as mentioned above, is an adequate supply of appropriate native seeds that will meet mandated establishment and cover criteria. For successful native seedings it is widely acknowledged that ecotypic (locally adapted and originating) native seeds must be used. In addition, quality, cleanliness, and consistency of native seed supply were perennial limitations to the department’s use of native seeds. This was in part because many available native seeds were either wild harvested or lacked quality control in production and marketing.

In the late 1990’s, the leadership and staff of TxDOT began advancing discussions with researchers, landowners, and seed producers toward addressing these limitations, particularly in South Texas where demand was especially acute for native plants as land uses shifted toward being wildlife-focused. Beginning in 2001 and continuing to the present, TxDOT, with partners including the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, USDA NRCS Plant Materials Centers, and Texas AgriLife Research began focused efforts to solve native seed supply and quality limitations, and to enable greater use of native plants for roadside plantings.

This partnership resulted in the South Texas Natives Project beginning work in 2001. Since 2011 this effort has expanded to serve the entire state through the Texas Native Seeds Program (TNS). TxDOT remains a signature sponsor of this effort, which has developed over 40 ecotypic native seed selections produced by Texas seed companies. The resulting Texas Department of Agriculture-certified origin and quality native seed are used for tens of thousands of acres of native plant restoration both on Texas roadsides and off by landowners and energy operators, especially for new oil and gas pipeline revegetation.

TxDOT currently specifies these native seeds for use in rural areas of two-thirds of Texas, and is currently supporting efforts led by TNS to provide needed seed supply for the Coastal Prairies and East Texas regions. Recent focus has also been on the development of seed supplies of pollinator- and monarch-plants for use throughout Texas on roadsides, including native wildflowers, perennial herbaceous plants, and milkweeds.

TxDOT is poised to continue working to promote native plants for Texas roadsides for years to come. The development and use of native seeds, diligent management of invasive species, and careful stewardship of right of way vegetation is a high priority of the agency and proud parts of the department’s legacy.

See also this video from TxDOT.

|

|

Commercial seed field of Zapata Rio Grande clammyweed, a pollinator and revegetation plant developed through the efforts of TxDOT and TNS.

Reseeding new right-of-way along US HWY-77 in south Texas. Credit: TxDOT.

|

|

|

Invaders of Texas Citizen Scientist and UT Graduate Student Study Techniques for Girdling Ligustrum

Since December 2013, Cliff Tylick has, with permission from the city of Austin, been leading projects to eradicate glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum) from close to 15 acres of Austin's Walnut Creek Metropolitan Park, which is located in northwest Austin. More recently, Alison Northup has worked with her neighbors along Boggy Creek by Downs-Mabsen Fields in east Austin, to remove glossy privet, too. Both parks, like so many others, are heavily infested with glossy privet.

In Austin's parks and greenbelts, volunteers can't use power tools or herbicides. So when it comes to privets, there are two choices:

• If they're small enough, uproot them.

• If they're too large to uproot, girdle them.

Alison, an ecology doctoral student in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College of Natural Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin, and Cliff, who is an Invaders of Texas citizen scientist in his spare time, met through iNaturalist and subsequently compared notes on their experiences with girdling glossy privet. They discovered that they both had had the same experience: the technique they'd learned from city staff hadn't killed any plants. The privets quickly covered the gap—whether 3 inches, 6, 12, or 24—in new bark, like scabs over a wound!

But some years earlier, Cliff had figured out a way that worked:

1. Using a carpet knife, make two parallel cuts around the trunk several inches apart, making sure to cut to the surface of the xylem, but no deeper.

2. Using a putty scraper, peel the bark and phloem away between those two cuts.

3. Finally, use the scraper to scrape any residual phloem and the film of cambium from the surface of the xylem to expose bare xylem.

Using this technique, he and his volunteers had killed hundreds of glossy privets in Walnut Creek Park. But every time he met with others doing girdling, they would tell him the same thing: They've girdled and girdled … and it doesn't work.

"We need to do an experiment," Alison said. "Girdle one group of ligustrums one way, girdle another group the other way, don't do anything to a third group, and observe what happens."

In the meantime, Cliff decided that he had to find a still better way, because scraping is hard on the hands and arms. "Every joint from my fingertips to my shoulders ached", he said. "One day I was explaining how to know when you're done, and I said the exposed sapwood should look like a clean wooden spoon. Then it occurred to me—if I had a wooden spoon covered in fibrous, slimy vegetable matter, I wouldn't scrape it. I'd wash it." So, by the time Alison and he did the experiment, they were also testing variants that included scrubbing with water, soapy water, or rubbing alcohol instead of scraping.

Alison designed the experiment to include six experimental treatments with 10 randomly selected privets in each. In mid-February, the privets were treated, and they will be monitored until it is clear whether they have bridged the gaps. They will also count shoots formed from the trunk below the girdle.

Preliminary results suggest their hypothesis that the more complex girdling techniques are better, but also that there are shoots appearing on some plants.

The research is supported by a grant from the Native Plant Society of Texas Austin Chapter. Cliff and Alison are deeply grateful to them for their support.

Interestingly, they've had queries about the technique from as far away as New Zealand. They plan to present their results in October at the annual conference of Texas Master Naturalists.

Stay tuned!

|

|

Alison Northup collecting data on girdled glossy privet. Credit: Alison Northup.

Examining girdled area for regrowth on glossy privet. Credit: Alison Northup.

Measuring regrowth in the girdled area on girdled glossy privet. Credit: Alison Northup.

|

|

|

Invasive Spotlight:

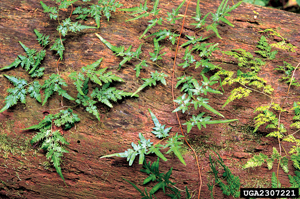

Japanese Climbing Fern

(Lygodium japonicum)

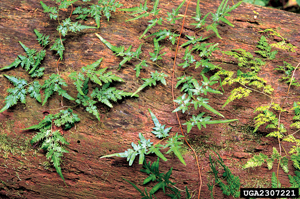

Japanese climbing fern is an invasive climbing fern that is changing the landscape of East Texas. An ornamental that is native to Asia and tropical Australia and was introduced from Japan in 1930s, it has escaped and is now rapidly spreading across the forested areas of Eastern Texas, smothering native trees and shrubs. Not only does it impact native vegetation directly, but it is also a significant fire hazard: the dead fern fronds serve as a fire ladder to carry fire to the crown of trees. It occurs in at least 25 East Texas counties.

Japanese climbing fern is a perennial viney fern, climbing and twining to 90 feet (30 m) long, with lacy, finely divided leaves along green to orange to black wiry vines. It can form mats of shrub- and tree-covering infestations. Tan-brown fronds persist in winter, while others remain green if warm enough. Its vines arise from underground, widely creeping rhizomes that are slender, black, and wiry.

As a fern, this invasive plant reproduces via spores. The spores can be carried miles by the wind, easily spreading the fern. It occurs along highway rights-of-way, and invades open forests, forest road edges, and stream and swamp margins.

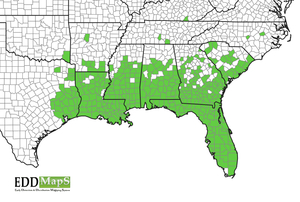

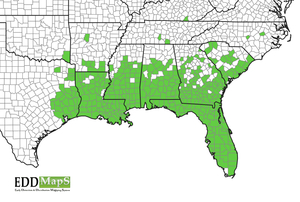

Because of its negative impacts, Japanese climbing fern is a Report It! species as part of the Sentinel Pest Network, a component of Texasinvasives.org. Please report any infestations of Japanese climbing fern you observe, particularly in counties not highlighted on this distribution map (click on Texas to see county map).

Follow this link for more information on the Japanese climbing fern.

|

|

Source: Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society

Photo credit: invasive.org

EDDMapS. 2016. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed April 29, 2019.

|

|

|

More News

Novel Hawaiian Communities Operate Similarly to Native Ecosystems

On the Hawaiian island of Oahu, it is possible to stand in a lush tropical forest that doesn't contain a single native plant. The birds that once dispersed native seeds are almost entirely gone too, leaving a brand-new ecological community composed of introduced plants and birds. In a first-of-its-kind study, researchers demonstrate that these novel communities are organized in much the same way as native communities worldwide. They also describe the complex benefits and costs of the invasive birds. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Science-Based Guidelines for Building a Bee-Friendly Landscape

Many resources encourage homeowners and land care managers to create bee-friendly environments, but most of them include lists of recommended plants rarely backed by science. To rectify this, researchers surveyed 72 native and non-native woody plant species in five sample sites throughout the Ohio Valley region to document which species attract which bees. Read more at sciencedaily.com, or see the presentation and other materials.

Invasive Crayfish Sabotages Its Own Success

Using a long-term dataset, researchers in Wisconsin have demonstrated that half of the study populations of rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) are declining. They found that the crayfish have altered their habitat such that there is less protection. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Harnessing Plant Hormones for Food Security in Africa

Striga (Striga hermonthica) is a parasitic plant that threatens the food supply of 300 million people in sub-Saharan Africa. Scientists have found that treating bare fields with a plant hormone that causes the parasite's seeds to germinate, they reduced the number of Striga plants. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Invasive Round Gobies May Be Poised to Decimate Endangered French Creek Mussels

The round goby (Neogobius melanostomus) -- a small, extremely prolific, invasive fish from Europe -- poses a threat to endangered freshwater mussels in northwestern Pennsylvania's French Creek, one of the last strongholds for two species of mussels, according to researchers. This is the first research focusing on the ecological impact of gobies on unionid mussels in a stream environment in the United States. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Adaptive Changes in an Invasive Caribbean Lizard

A remote island in the Caribbean could offer clues as to how invasive species are able to colonize new territories and then adapt in them, suggests a new study on the non-native Maynard's Anole (Anolis maynardi). Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Antarctica: The Final Frontier for Marine Biological Invasions?

A new study looking at the implications of increased shipping activity and its impact on Antarctic marine biodiversity is an important step in the quest to understand whether invasive species, introduced by shipping, will find the Antarctic marine environment more hospitable as Antarctica's climate changes. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Massive Ecological and Economic Impacts of Woody Weed Invasion in Ethiopia

Scientists have documented the massive ecological, social and economic impacts that the invasive alien tree Prosopis juliflora has had across the Afar Region of north eastern Ethiopia. The tree, a species of mesquite from the Americas, was intentionally planted to provide wood for charcoal, fodder, and timber and to minimize erosion. Read more at sciencedaily.com.

Lionfish Genes Studied for Clues to Origin

A new genetic study of red lionfish (Pterois volitans) from both the Pacific from where it originates and the Atlantic where it has invaded sheds light on from where in the Pacific the Atlantic fish came, and whether they are hybrids with the devil fire fish (P. volitans). Read more at sciencedaily.com.

|

|

|

If you would like to highlight a successful invasive species project or nominate a special person to be highlighted in an upcoming iWire, please send the details to iwire@texasinvasives.org.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sentinel Pest Network and Invaders of Texas Species Workshops

Invaders of Texas workshops train volunteers to detect and report invasive species as citizen scientists. Workshops, which are free, are designed to introduce participants to invasive species and the problems they cause, cover aspects of invasive species management, and teach identification of local invasive plants, and to train participants to report invasive plants using the TX Invaders mobile application. The workshop is 7 hours long (usually on a Saturday, but scheduling is arranged with each individual host group). The workshop satisfies Master Naturalist training requirements.

Sentinel Pest Network workshops serve to increase the awareness and early detection of a set of particularly important invasive species, to help prevent their spread into Texas or their further spread within Texas. Participants learn to identify species such as the Emerald Ash Borer, Cactus Moth, Asian Longhorned Beetle, and other pests of regulatory significance, and to report them. The workshop is 3.5 hours long. The workshop satisfies Master Naturalist training requirements.

Upcoming Workshops:

Saturday, May 10, 2019

Invaders of Texas Workshop

Location: St. Michael's Catholic Church (Jasper, TX)

Contact: Lori Horne

Note: This workshop has a fee.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

Invaders of Texas Workshop

Location: Houston Advanced Research Center (The Woodlands, TX)

Contact: Teri MacArthur

For more information or to register to attend a free workshop, please visit the Workshop Page. |

|

|

|