|

April 2022

|

|

|

A Crazy Fungus

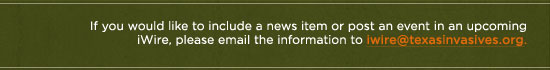

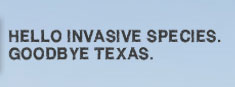

Tawny crazy ants (Nylanderia fulva) have been spreading across Texas and North America for the last 20 years. They quickly displace native ants, invertebrates, and animals, even other invasives, like the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta). These golden-brown ants are called crazy ants because of the erratic, random way they move. They lack a stinger, instead relying on a formic acid spray. They are known to cause problems for lizards, birds, mammals, livestock, and electrical equipment. They attack animals around the eyes, nasal fosse, and hooves. Often these attacks lead to blindness or asphyxia in smaller animals. Large numbers of tawnys often accumulate in electrical equipment, clogging the switching mechanism, causing short circuits and equipment failure. As a social insect, they are found in large colonies or super colonies (groups of colonies that are indistinguishable from each other). These populations can grow to overwhelming numbers, and we have little in out arsenal to combat them. Until now.

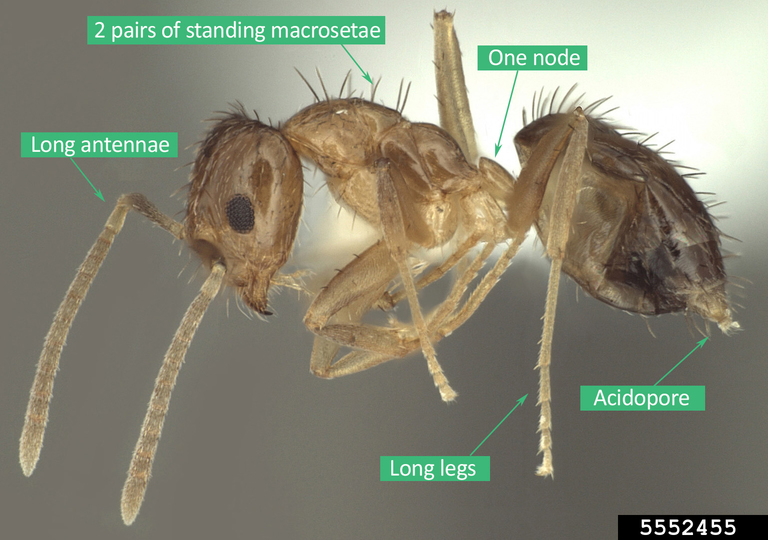

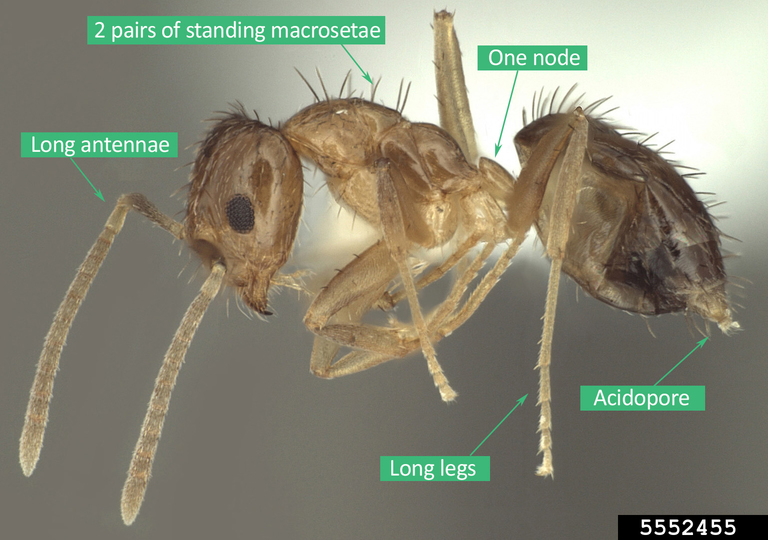

Social insect populations exhibit a boom-bust dynamic that allows a colony to experience a population decline (due to various external stimuli) and then bounce back with ease. This makes colonies very difficult to control or eradicate (insecticides have little to no effect on the colonies). Recent research has found a microsporidian pathogen that may change all of that. Spores from a naturally occurring fungus were found in tawny crazy ants when scientists noticed workers with abdomens swollen with fat. Upon closer examination, they found the fugal pathogen, Myrmecomorba nylanderiae, a species new to science. Microsporidian pathogens take over an insect’s fat cells and use them for spore production. Myrmecomorba nylanderiae seems to shorten the lifespan of the workers, affecting the flexibility of the boom-bust dynamics and leads to population decline. Shorter worker life span could make it harder for populations to survive winter. The fungal pathogen has led to population extinction in 62% of infected populations. This microsporidian does not infect other ant species or arthropods, making it a great option as a biocontrol agent. So far, M. nylanderiae infected ants have been introduced to two different tawny crazy ant populations that were very large and out of control. Within a few years, the fungal pathogen had wiped them out. Although it is not an instant “kill -all” solution and is very labor intensive, it is a new weapon in an armory that used to be empty.

Read the research: LeBrun et al., 2022

Read more about Tawny crazy ants here.

|

|

Tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva). Credit: Danny McDonald. Tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva). Credit: Danny McDonald.

Microsporidia spores (Myrmecomorba nylanderiae) collected from tawny a crazy ant in central Texas. Credit: Edward LeBrun, University of Texas at Austin. Microsporidia spores (Myrmecomorba nylanderiae) collected from tawny a crazy ant in central Texas. Credit: Edward LeBrun, University of Texas at Austin.

Collecting tawny crazy ants in the field. Credit: Thomas Swafford, University of Texas at Austin. Collecting tawny crazy ants in the field. Credit: Thomas Swafford, University of Texas at Austin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flying Monks

Monk parakeets (Myiopsitta monachus), also known as quaker parrots, are native to Brazil and started their life in Texas as a beloved exotic pet before breeding pairs escaped or were released. Now, they can be found throughout many of Texas’s urban areas.

The monk parakeet is a “chunky” parrot with a long tail. It is bright green with a lower chin and chest of gray feathers. This bird is fairly large, growing up to 11-12 inches in length. They build large stick nests that contain multiple apartments, providing space for up to 12 pairs. They can be seen tussling with each other and grackles, and their squawking call can be heard cat-calling passing pedestrians.

The first monk parakeets were observed in the 70s. They seemed to be expanding quickly throughout the U.S., with accounts describing them in the 4000-5000s. Since they were perceived to be a danger to agriculture, and many feared they would become the next European starling (Sturnus vulgaris), many states organized to eradicate them; however, only a few hundred were found and removed before fears subsided and control attempts discontinued. In Texas, many breeding colonies and wondering singles can still be spotted. There are colonies in the southwest suburbs of Austin, in the southwest suburbs of Houston, and on the transmission towers over Expressway 146 near Kemah. Nests that weigh up to 400 pounds can often be seen on the top of cell towers and telephone poles. Small flocks and/or single monk parakeets have also been seen in Galveston, Montgomery, Llano, Tarrant, and Hookley County. San Leon has adopted the bird as the mascot for a local distillery. There are even accounts of single monk parakeets seeking out human companionship, adopting the person by landing on their head or shoulder.

Many species of parrot and parakeets have been accidently released into the wilds of Texas and the U.S., but few have carved out a niche as successfully as these exotic green birds.

|

|

Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Credit: Stephanie Sanchez. Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Credit: Stephanie Sanchez.

Monk parakeet nest. Credit: John J. Mosesso. Monk parakeet nest. Credit: John J. Mosesso.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Honey bees, Bred for Better Things

Varroa mites (Varroa destructor) have been the prime threat to honey bees since their introduction 50 years ago. This small arachnid (about 0.6 inches wide) is an external parasite of honey bees (Apis spp.). Varroa’s have a flattened and oval body and eight legs. Adult females are reddish brown and males are yellowish with tan legs. Males are smaller and more spherical in shape. These mites originated from Asia and were only ectoparasites of the Asian honey bee (Apis cerana) until it evolved the ability to parasitize European honey bees (Apis melifera). European honey bees have not built up a resistance to these invasive mites. Heavy mite infestations can cause malformed wings, legs, and bodies in newly emerged bees. Parasitism in adult bees affects flight, orientation, and can cause bees to get lost, preventing them from returning home. The loss of worker bees severely weakens the colony. Weak colonies are susceptible to robbery by stronger hives. Eventually, the colony dies. Varroa destructor also carries several viruses that are fatal to bees including: deformed wing virus, acute bee paralysis virus and slow paralysis virus. These viruses result in a condition called “parasitic mite syndrome” and a colony can be destroyed in a few months. Methods for controlling the mites, and the diseases they carry, have had limited success, and the varroa mites’ resistance to chemical treatments is increasing. Desperate for a solution, the Agricultural Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) began to breed honey bees for resistance to the varroa mite. This rigorous breeding program lasted for 20 years and has shown promising results. The mite resistant bees were named "Pol-line" bees. Pol-line bees were twice as likely to survive the winter (60% survival) compared to standard honey bees (26% survival). High losses were experienced in standard honey bees unless extensive chemical miticide treatments were initiated. The mite resistant colonies also show a level of resistance to three of the major viruses: deformed wing virus variant A and B, and chronic bee paralysis virus. Although further investigation is required, the results have demonstrated, thus far, a strong potential for varroa resistance and the reduction of colony loss.

Read the research: O’Shea-Wheller et al., 2022

|

|

Varroa mite ( Varroa destructor). Credit: Scott Bauer.

Adult female varroa mite feeding on a developing honey bee. Credit: Scott Bauer.

Worker bee with deformed wing virus due to severe varroa mite infestation. Credit: Klaas de Gelder.

|

|

|

|

|

|

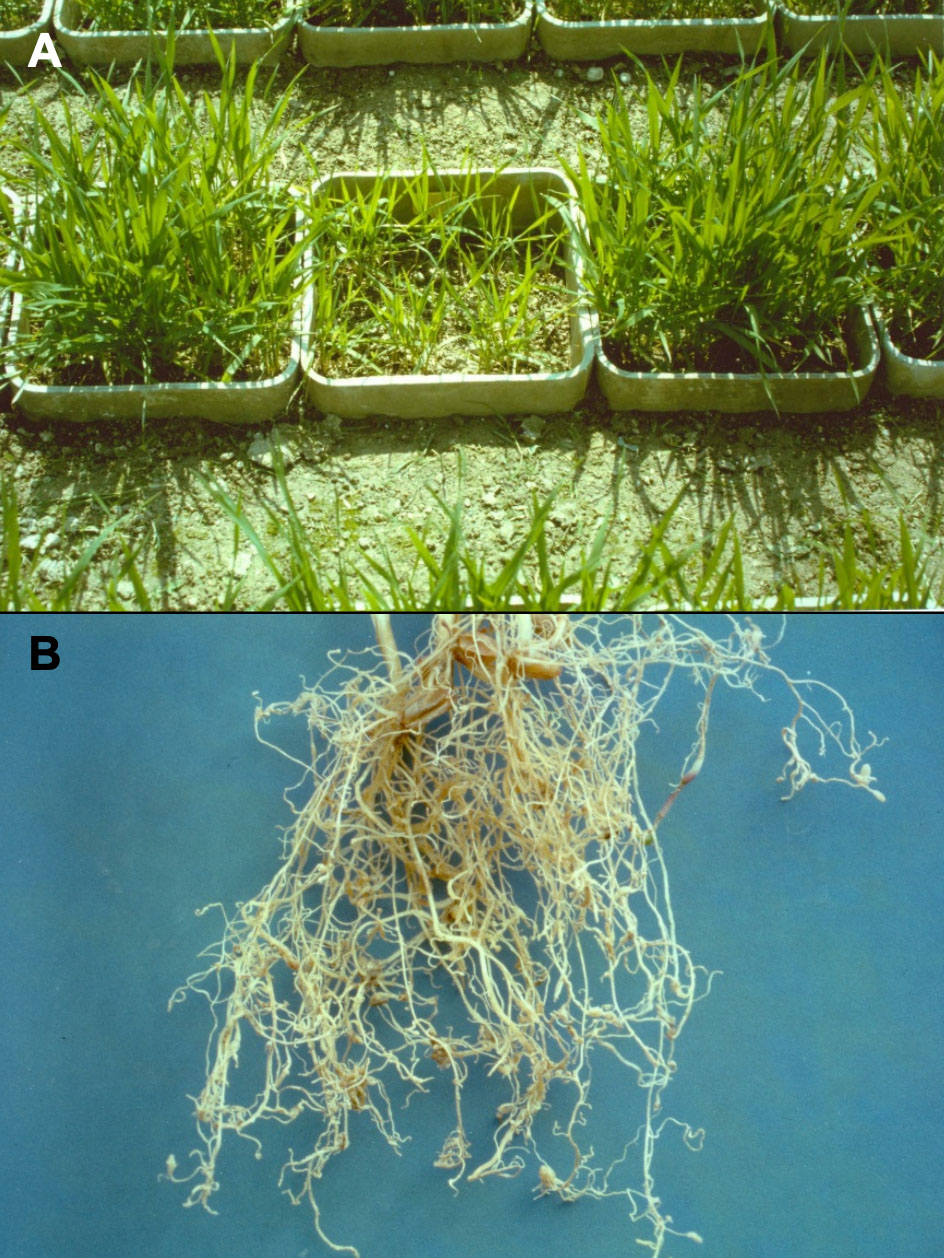

Are You Eating My Crops? 12 of 12

British root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne artiellia) are known to infect 2000 plant species world-wide and account for 5% of global crop loss. We have reached the end of our 12-month series called ‘Are you eating my crops?’ Individual pests highlighted in this series have not yet been reported in Texas, but are on the ‘Watch List’ due to their high level of pest importance or risk due to host availability. So far during this series, we have covered several different crop pests, what damage they cause, what they look like, and where you can find more information about them. To read about previous headliners, visit TexasInvasives.org and look under the field crop pest survey tab.

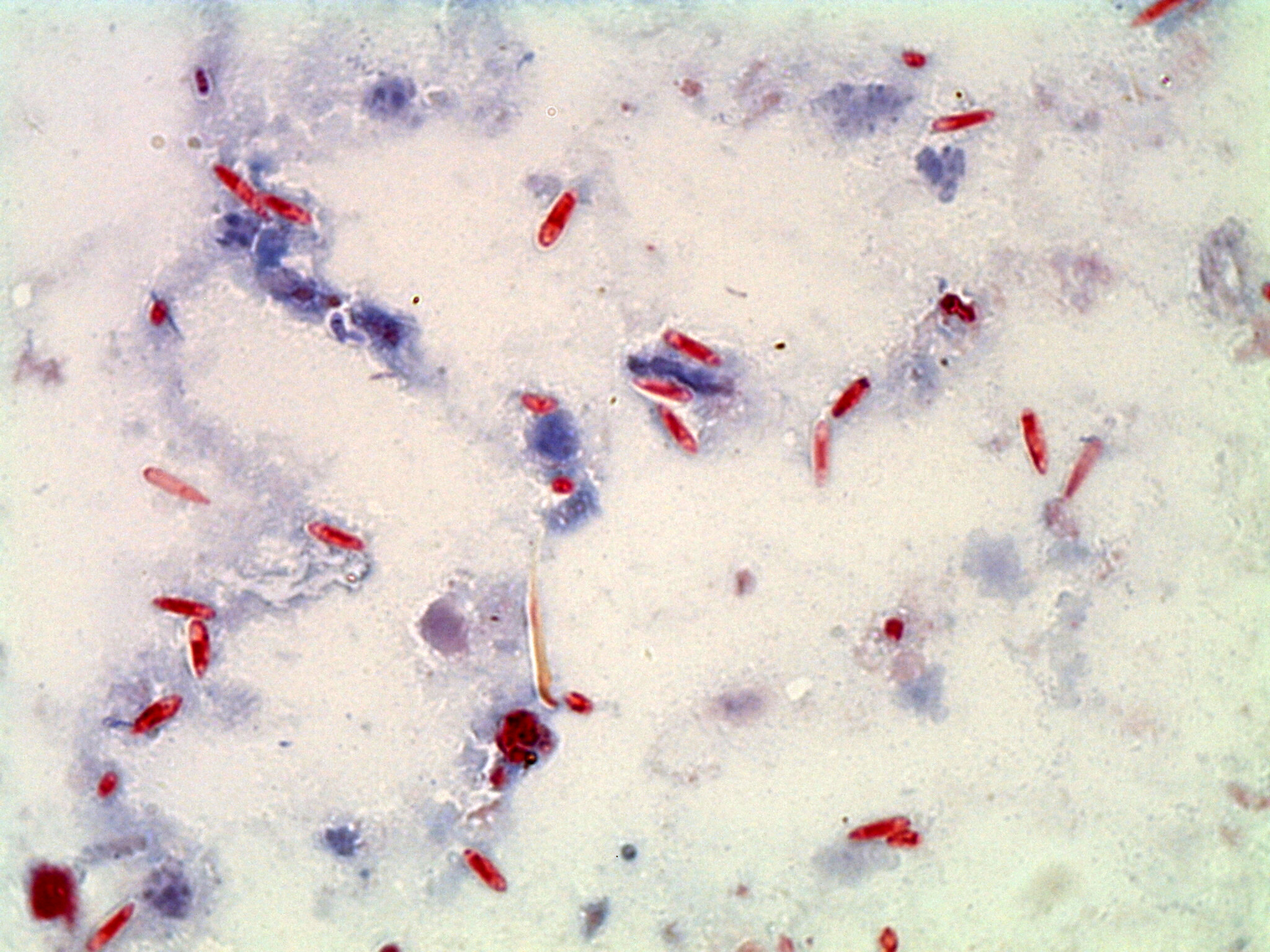

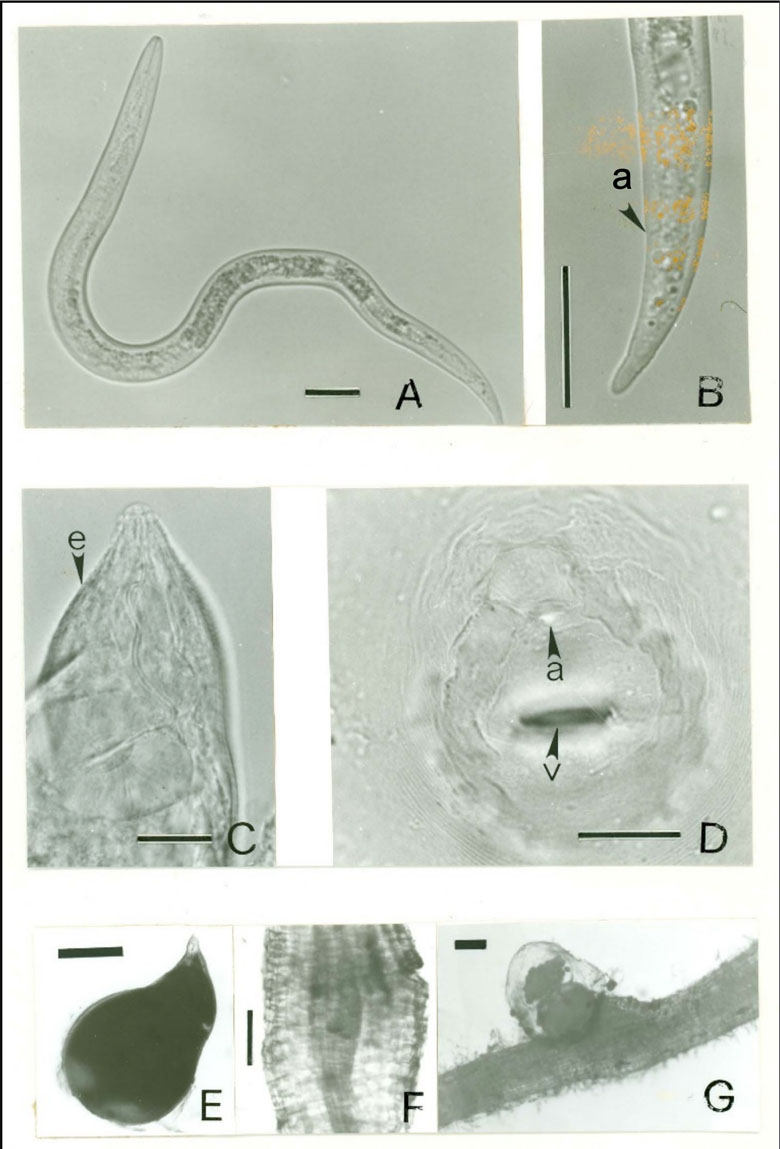

Meloidogyne artiellia is a microscopic plant parasitic nematode. The females grow to be 650-750 µm in length, while the males only grow to 0.82-1.37 µm in length. The adults exist in the soil and the larvae infect plant roots. There are four juvenile larval stages (J1-J4). The first stage starts inside the egg, followed by a molt and emergence when the second stage moves out of the egg and invades the host plant roots. This is the only stage when juveniles are mobile and can live for a short time in the soil. They will then either reinfect the same root system they hatched from or find a new system to infect. The J2 moves into the roots where it eventually becomes sedentary and forms feeding cells, also known as giant cells. Juveniles will feed from the giant cells for about 24 hours after becoming sedentary. The feeding cells contaminate the root and cause the surrounding root tissue to form a gall in which the J2 is embedded. This can cause the young to die and mature plants to decreased yield. Satiated from feeding, the J2 molts three times into adults. Female adults will resume feeding. For the next three months the adult female will produce squishy egg sacs that can hold 500-1000 eggs. The egg sacs are deposited on galled root surfaces or inside root galls. Emergence from eggs typically happens under moist soil conditions. Eggs will not hatch if conditions are too dry; instead, they will remain dormant until conditions improve. Eggs can also be distributed by irrigation ditches.

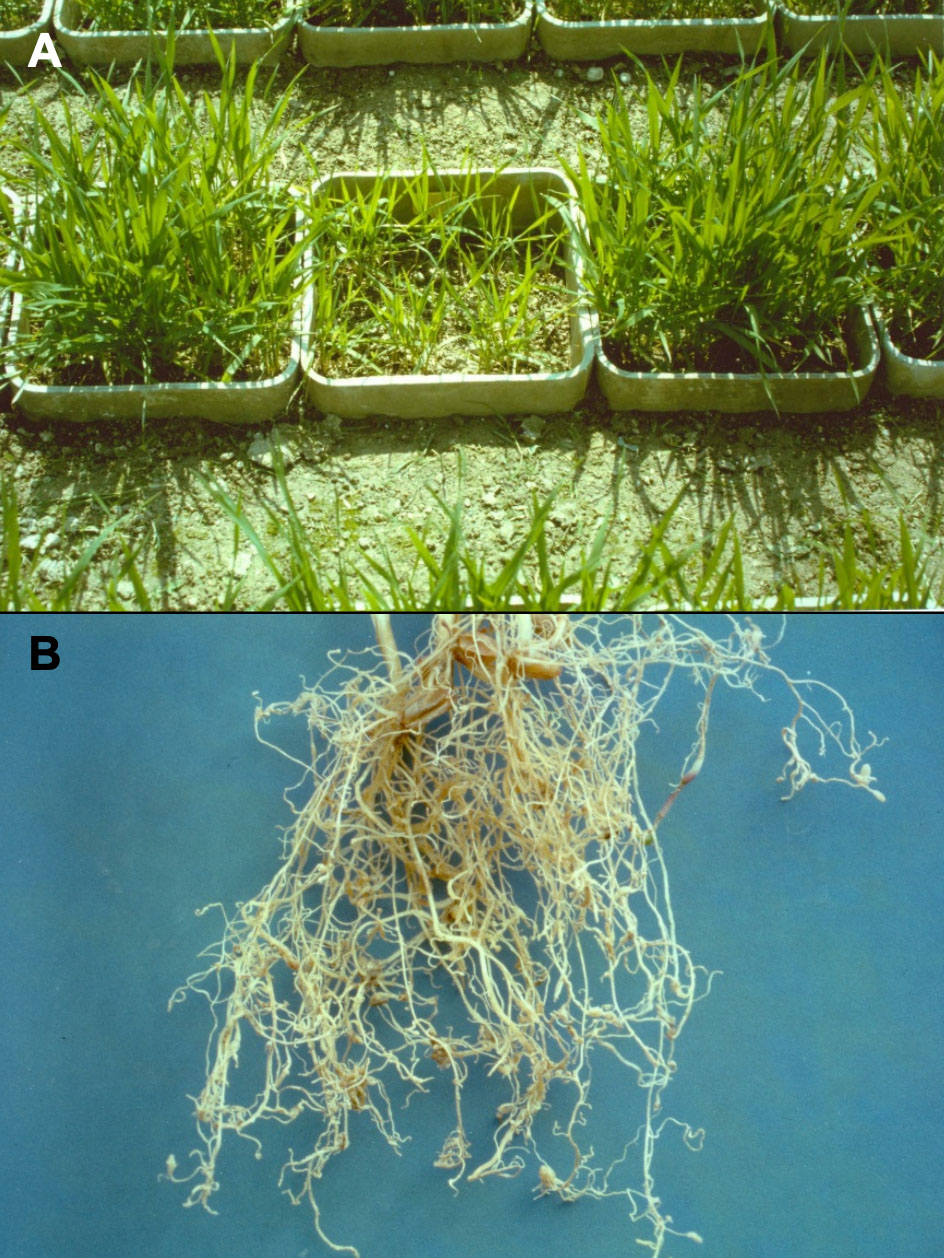

Thousands of plant species are susceptible to M. artiellia, but the most common host plants infected are cereals, crusiferae (mustards), and leguminosae (peas and bean family). Damage due to infection involves impaired root growth and impaired root function. Symptoms are similar to those caused by nutrient or water deficiency. Plants may appear withered under sunny conditions even if there is sufficient soil moisture. This is because infestations limit water intake, and the development of root-knot galls drains the plants of photosynthate and nutrients. Injured root tissue is also susceptible to disease-carrying pathogens.

British root-knot nematodes can be easily confused with other nematodes and require morphological identification to distinguish them from other species. To learn more, click here. If you believe you have seen plants that bare signs of a M. artiellia infestation, please email invasives@shsu.org with an image and a location.

|

|

Photomicrograph of Meloidogyne artiellia life stages. A) Entire body of second-stage juvenile (J2). B) Posterior body portion of J2, a=anus. C) Anterior body portion of swollen female, e=excretory pore. D) Perineal pattern showing the eight-shaped inner area marked by coarse lines and containing vulva (v) and anus (a). E) Entire body of swollen female. F) Slight swelling induced by J2 on chickpea root. G) Large egg mass covering a swollen female, which protrudes with its posterior portion of the body from the surface of a chickpea root. Credit: R.N. Inserra.

Damage cause by M. artiellia. A) Stunted hard wheat plants seen in center. B) Infected hard wheat roots. Note: the small galls on the roots. Credit: R.N. Inserra.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Boating Season Reminders

With summer approaching and temperatures rising, boating season and recreational water time is just around the corner. Here are a few things to keep in mind while you’re having fun that will prevent the spread of aquatic invasive hitchhikers.

Implement the clean, drain, and dry method to any watercrafts, trailers, or recreational equipment! Clean visible plants, mud, and large-bodied organisms that are in or on the watercraft/equipment. When possible, rinse equipment and boat hulls with high pressure, hot water. Then, rinse the interior compartments of boats with low pressure, hot water (120°F). Flush motors with hot water (120°F) for about 2 minutes. Drain all water. Residual water can hide small and microscopic invasive organisms, such as pieces of giant salvinia or zebra and quagga mussel larvae. Let everything dry before moving to another body of water to ensure that living material is not being moved. Many organisms can survive in small amounts of standing water. Dry time varies, but can take up to 5 days. Some lakes have cleaning stations available to aid in washing away the invasives. Also, don’t dump your bait. This can introduce invasive species into the ecosystem.

Following these simple steps are paramount for keeping our waterways clean and healthy. For more information, visit the clean, drain, dry information page.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two Houston Area Events

Smarter About Sustainability Seminar 2022

May 14 @ 9:00 am- 12:00pm

Join local experts to explore the current state of our local environment, potential threats, and opportunities for you to help keep those threats at bay. This workshop is FREE, but registration is required. Click here for additional information.

Wildscape Workday at Sheldon Lake State Park

May 21 @ 8:30 am - 11:00 am

The Wildscape garden area is a great opportunity to help with raking, weeding, removing invasive species, and planting, as well as learn a little more about native species in Texas and garden maintenance. No registration necessary. All volunteers welcome. Click here for additional information.

|

|

Credit: KNKleiner, TRIES

|

|

|

|

|

|

Invasive Spotlight:

Brazilian Peppertree

(Schinus terebinthifolius)

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthololius) is a broadleaf evergreen that can grow up to 30-40 feet high, with a trunk diameter of up to 3 feet. This small tree has a tangle of branches that grow away from multiple trunks and out into a twisted array of vegetation. Due to a growth process called basal sprouting, Brazilian pepper trees can have dozens of trunks instead of one. Yellow-green stems sprout alternating dark green leaves that are pinnately compound with 3-13 leaflets, each 1-2 inches long. Crushed leaves emit a peppery or turpentine-like fragrance. Flowers grow in small clusters and have 5 white petals and a yellow center. Fruit are small red berries, 1/8-1/4 inch in diameter. Male and female flowers bloom from September to November, and fruit from December to February. Seed are dispersed by birds, mammals, and flowing water. The tree can also propagate via advantageous buds sprouting from roots.

This plant is considered one of the greatest threats to native biodiversity for its dramatic effect on both plant and animal communities by reducing quality of life. It is a TDA noxious weed and a TPWD prohibited exotic species. The intertwining, drooping branches and foliage forms dense thickets that shade out native grasses, smother the native vegetation and affect the local animal community. The tightly grown thicket provides a poor habitat for native species. Brazilian peppertrees are closely related to poison oak and poison ivy (all in the family Anacardiaceae). Those that are allergic to poison oak and ivy will likely be allergic to the peppertrees.

The Brazilian peppertree thrip (Pseudophilpthrips ichini) is a new potential biological control agent that could help with the Brazilian peppertree problem. These thrips have been studied for over two decades in Florida. Host specificity experiments demonstrate that it has a limited host range and can cause a severe reduction of Brazilian peppertree biomass. They were released in certain Florida counties in 2019. Recently, some Texas counties with Brazilian peppertree overgrowth have received USDA APHIS approval for release. We could see release dates and biocontrol projects begin as soon as this year. To learn more about the Brazilian peppertree thrips, click here.

These trees can be found in Texas and are actively taking over the coastal plains. To learn more about the Brazilian peppertree and management options visit the TexasInvasives info page. If you believe you have found a Brazilian peppertree, please report it to invasives@shsu.edu.

|

|

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthololius) leaves and berries. Credit: Amy Ferriter.

Brazilian peppertree basal sprouting. Credit: Forest and Kim Starr, Starr Environmental.

Pseudophilothrips ichini, biological control for Brazilian peppertrees. Credit: James P. Cuda.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Opportunities To Get Involved

Looking for participants for the following surveys:

Citrus Greening Workshops

We need your help to safeguard Texas Citrus, and it can start in your backyard!

TISI is offering educational workshops focused on the Asian citrus psyllid and the pathogen Citrus Greening. The Asian citrus psyllid and the Citrus Greening pathogen is threatening citrus in multiple Texas counties, and we need your help to monitor the spread. The workshop will highlight what you need to look out for, address USDA-APHIS Citrus Quarantines, and offer diagnostic services if you suspect your backyard citrus has either the psyllid pest or Citrus Greening pathogen. This includes providing trapping materials, assisting with management strategies, and more.

Please contact invasives@shsu.edu so we can schedule a workshop (virtual or in-person) for you or your group this year!

Aquarium Watch: Looking for Prohibited Invasive Aquatic Species

Please help texasinvasives.org and natural habitats by looking for 14 prohibited invasive aquatic species being sold in your local aquarium store. With just one photo you can assist us in finding and documenting which stores are selling prohibited species. Texasinvasives.org will contact the appropriate Texas institutions to remove the species for sale.

If you would like more information please email invasives@shsu.edu, and mention you want to assist with our Aquarium Watch.

Air Potato Survey

Help Texas Research Institute for Environmental Studies conduct an air potato survey by actively reporting any infestations seen in your area. The air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera) is a fast growing, high climbing vine. Potato-like tubers are the primary means of reproduction for this vine. They can be as small as a marble or as large as a softball. Native yams are often confused for air potatoes, to avoid this confusion please refer to the key below:

- Plants rhizomatous; bulbils never produced in leaf axils; petiole base never clasping the stem; Native D. villosa

- Plants tuberous; bulbils produced in leaf axils; petiole base sometimes clasping the stem; Invasive D. bulbifera

For additional information, please refer to the TexasInvasives information page.

If you believe you have identified an air potato vine, please email invasives@shsu.edu and include the following information: an image, an approximate number of vines present, the location (including whether it is on public or private land), and if bulbils are present (the potato-like tubers that emerge from the stem). |

|

Leaf mottle on grapefruit, a characteristic symptom caused by citrus greening bacterium but also seen on trees infected by Spiroplasma citri. Credit: J.M. Bove.

Armored catfish ( Hypostomus plecostomus). Credit: United States Geological Survey.

2%20bulbil.%20credit%20Karen%20Brown.jpg)

Air-potato (Dioscorea bulbifera), bulbil emerging from leaf axil. Credit: Karen Brown.

|

|

|

|

|

|

More News

Here Are 10 of the Peskiest Invasive Species in Greater Houston

There are dozens of invasive plant, animal, and insect species in Texas. They all threaten native species and lead to several environmental concerns. Here is a list of the top ten invasive nuisances found in Houston. houstonpublicmedia.org

Feds Seek to Protect Rare Texas Plant in the Path of Border Wall Construction

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed to list the prostrate milkweed (Asclepias prostrata) as an endangered species. This rare plant, found along the Texas-Mexico border, is threatened by the growth and spread of invasive grasses, and by boarder security activities and construction. texastribune.org

What Makes this Invasive, Non-Native Reed Grass Thrive in the Wetlands?

Researchers closely examined the genomic bases of Phragmites australis ssp. australis, or the common reed, in order to determine how this invasive thrives in wetlands, compared to its native counterpart, Phragmites australis ssp. americanus. phys.org

Wildlife Agency Turning Invasive Water Hyacinth into Organic Fertilizer

A 35-acre pilot program has been launched in Florida to find a way to successfully clear a body of water of common water hyacinth without using chemicals or other extreme measures. wusfnews.wusf.usf.edu

Nanoparticles Prove Effective Against the Yellow Fever Mosquito

Mosquitos have evolved a natural resistance to many of the available insecticides. Scientists are working to offer an alternative option. Carbon black is a nanoparticle that could aid in the fight against yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti). phys.org

In Western Floodplains, Species Adapt to Bullfrog, Sunfish Invaders

A new study of a southwestern Washington floodplain finds that most native species adapt well to the presence of invasives, like the American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) and sunfish (Centrarchids), by shifting their food sources and feeding strategies. sciencedaily.com

Scientists Develop a Plan to Manage Lionfish Populations in the Mediterranean

Scientists have published a Guide to Lionfish Management in the Mediterranean, which features a series of recommendations they hope can be used to manage lionfish (Pterois miles) populations. phys.org, plymoth.ac.uk

The Worrying Arrival of the Invasive Asian Needle Ant in Europe

The territory of the invasive Asian needle ant (Brachyponera chinensis) has continued to expand over the last 80 years, this expansion includes 17 U.S. states. Europe has just been added to the list. sciencedaily.com

Callery Pears: An Invader 'Worse Than Murder Hornets!'

Callery pear trees (Pyrus calleryana) are a popular landscape trees that are spawning aggressive invaders, creating thickets that overwhelm native plants, provide poor habitat for birds, and sport nasty four-inch spikes. galvnews.com

In 'Plant Armor' Crop Cover, Insects Have to Navigate Textile Maze

A new textile 'Plant Armor' forces insects to navigate through a maze-like path. The design was more effective at blocking insects from reaching plants in multiple experiments, compared to alternative crop covers. sciencedaily.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you would like to highlight a successful invasive species project or nominate a special person to be highlighted in an upcoming iWire, please send the details to iwire@texasinvasives.org.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sentinel Pest Network and Invaders of Texas Workshops

Invaders of Texas workshops train volunteers to detect and report invasive species as citizen scientists. Workshops, which are free, are designed to introduce participants to invasive species and the problems they cause, cover aspects of invasive species management, teach identification of local invasive plants, and train participants to report invasive plants using the TX Invaders mobile application. The workshop is 7 hours long (usually on a Saturday, but scheduling is arranged with each individual host group). The workshop satisfies Master Naturalist training requirements.

Sentinel Pest Network workshops serve to increase the awareness and early detection of a set of particularly important invasive species to help prevent their spread into Texas or their further spread within Texas. Participants learn to identify species such as the Emerald Ash Borer, Cactus Moth, Asian Longhorned Beetle, and other pests of regulatory significance, and to report them. The workshop is 3.5 hours long. The workshop satisfies Master Naturalist training requirements.

Upcoming Workshops:

Smarter about Sustainability Virtual

May 14, 2022

9am-12pm

Registration link: https://environmentalservicesdepartment.wufoo.com/forms/kk2qdwz0k3rgh2/

|

|

|

|

Tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva). Credit: Danny McDonald.

Tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva). Credit: Danny McDonald. Microsporidia spores (Myrmecomorba nylanderiae) collected from tawny a crazy ant in central Texas. Credit: Edward LeBrun, University of Texas at Austin.

Microsporidia spores (Myrmecomorba nylanderiae) collected from tawny a crazy ant in central Texas. Credit: Edward LeBrun, University of Texas at Austin. Collecting tawny crazy ants in the field. Credit: Thomas Swafford, University of Texas at Austin.

Collecting tawny crazy ants in the field. Credit: Thomas Swafford, University of Texas at Austin. Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Credit: Stephanie Sanchez.

Monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Credit: Stephanie Sanchez.  Monk parakeet nest. Credit: John J. Mosesso.

Monk parakeet nest. Credit: John J. Mosesso.

2%20bulbil.%20credit%20Karen%20Brown.jpg)